THE MAN FROM NOWHERE

Jesus has no origin story in Mark’s Gospel, but in a matter of lines, we learn things about him and about life of timeless worth

Every writer setting out on a film script for a famous character is faced with the dilemma: do they use the movie’s precious time to tell the origin story? I have watched two Spiderman films with different actors where Peter Parker’s back story – how he acquired his superpowers – have been explained at length. This is not easy for an arachnophobe. The Joker has been portrayed by Jack Nicholson and Heath Ledger in Batman films. His origin was explained in full in the former, but emerged fully formed in the latter, as if there was no time to waste.

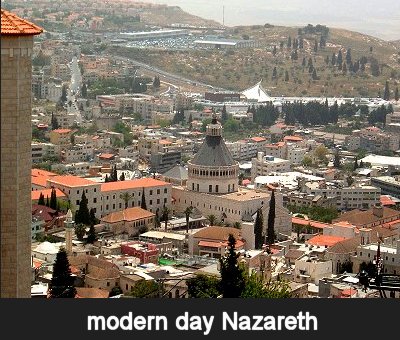

St Mark would have some sympathy with Heath Ledger’s Joker. At the start of his Gospel, Jesus appears from nowhere, fully formed. Unlike Matthew and Luke, who took the best part of three long chapters to explain the birth and early years of Jesus, Mark simply says: ‘In those days Jesus came from Nazareth in Galilee’. His Gospel is terse. No words are wasted explaining things. It is so different to our over-stated world where the sentence Jesus came from Nazareth would likely be followed by eight exclamation marks: !!!!!!!! Mark knows there is no need to exaggerate Jesus. In fact, the observation that he came from Nazareth is about as cool as saying you come from Slough or Croydon; my apologies if you do. Jesus effectively came from nowhere, which is how God wanted it.

The first thing we learn about Jesus’ character is his humility. Instead of announcing his greatness, he allows himself to be ministered to by someone else; to go through the act of baptism like every believer. But Mark is not slow to identify who Jesus is, because only words later he has God tear open the sky to proclaim Jesus as his Son, deeply loved. If the story had stopped there and we had been asked to continue it without knowing what would come next, it’s unlikely we would have taken Jesus out to the wilderness. If God’s Son has arrived, we would have placed him in Jerusalem, healing people and taking on corrupt leaders like his forerunner, Elijah. Why take him from boring Nazareth to a vast empty space? Mark does not answer this question. It is left to Matthew and Luke, again, to explain the monumental battle Jesus went through in the desert with the forces of darkness; how he won an early and decisive fight against the corruption of power. If we had only Mark’s Gospel, we would be scratching our heads, trying to fill in the back story of Jesus in the wilderness. Yet there is something powerful in this account.

After years of growing up, Jesus would have had an emerging sense of his destiny. He was fully human, but did not come into the world fully formed. He grew like every other child, learning from family how to socialise and how to make sense of the world; developing skills that could be put to use in adult life. Jesus, as expected of him, went into the family trade. But he must have grown to know there was a different path to take. His relatives clearly did not find this easy, but Jesus broke the family mould.

In doing this, he needed confirmation this was the right thing to do. At his baptism, the voice from heaven was a life-changing, exhilarating moment. God was with him. More than that, God was in him, and he in God. Most of us, after a wonderful event, take time to look back and savour it; to talk it through and bask in its significance. Yet Mark says ‘the Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness’. Jesus is unceremoniously dumped in the middle of nowhere and asked to find food and water, to fend off wild animals at night and face down Satan in fight he could not afford to lose. Some way to show your child you love them!

But there is meaning for us in this. How many times have we experienced great moments of joy and happiness, only for them to be followed quickly and unceremoniously by crashing, inexplicable lows? Many who minister in the Church can attest to this; most of us in life know how easily life turns for the worse. Like a football crowd, we are still celebrating a goal when the other team goes up the field and scores for itself. I don’t know why life is so bi-polar, but in Jesus we have someone who has experienced it up front and personally. The most wonderful baptism in world history is followed by scorching days and freezing nights in the desert, all alone.

Mark does not give us an answer why Jesus had to do it this way and many of us have to cope with sudden reversals of welfare that leave us wondering where God is in our lives or, in the words of President Bartlet in TV’s West Wing, makes us think he ‘just vindictive’. What might be said is this: life is a hazardous journey for most of us. The highs we experience – those times of joy and fulfilment, when we have a sense of purpose, of having made a difference – give us memories that can help us with the lows that follow – those moments of loneliness and despair, when our lives feel directionless and without meaning. They remind us that God has been doing things in our lives and will do so again. Our faith is often tested like the hull of a spacecraft entering the earth’s atmosphere, subject to fierce heat, before we can find our feet on the ground again.

The lows also help to make us more humble and to value the highs when they re-appear. People who have good fortune in this world, where most things seem to go right, can become careless and arrogant about it. They are tempted to attribute their good luck to being better than others and begin to divide the world up into those horrible categories of winners and losers. If you have ever walked in darkness, wondering where God is, you are much better fitted to help others who do than someone who has never suffered this way.

We don’t have any physical deserts to inhabit in the UK, but anyone who has spent even a short time in one knows it cuts you ruthlessly down to size. The heat, the lack of any protection from the sun, the absence of water, the sheer untamed size of the space, full of sand and rocks, tells you this is a place you cannot afford to spend much time in without support, before your welfare is put at risk. Around us there are people are wandering in their own desert. Not a literal one, but lives they feel trapped in, which oppress them and tempt them to lose hope. When Jesus went into the desert, there is no suggestion in Mark’s Gospel that he knew how long he would have to spend there. We know it would be forty days, but did he?

When people wander, bewildered, in their own desert in life, there is always the temptation to offer pastoral care and support in a way which rushes people out of it. Don’t worry, we say, it’ll soon be over. But the person stuck in the desert doesn’t feel this, just as I expect Jesus didn’t. We must spend time with them as they stagger through and linger with them there. No-one is inspired by being shouted at from a distance to get a move on. True encouragement in God is whispered in the ear, as we walk step by step with others in their pain.

POPULAR ARTICLES

Obama's Covert Wars

The use of drones is going to change warfare out of all recognition in the next decades.

Through A Glass Starkly

Images of traumatic incidents caught on mobile phone can be put to remarkable effect.

What Are British Values?

Is there a British identity and if so, what has shaped the values and institutions that form it?